September 12, 2018 - In Europe, Bjarke Ingels Group’s innovative approach has created buildings that feel like villages. Can they replicate that in North America?

“If everyone is different, then why do so many buildings look the same?” asks Danish architect Bjarke Ingels. “That’s something we’ve been thinking about for a few years now.” It’s an excellent question – and as our cities absorb new development in the form of apartment buildings, how can those buildings create a sense of community?

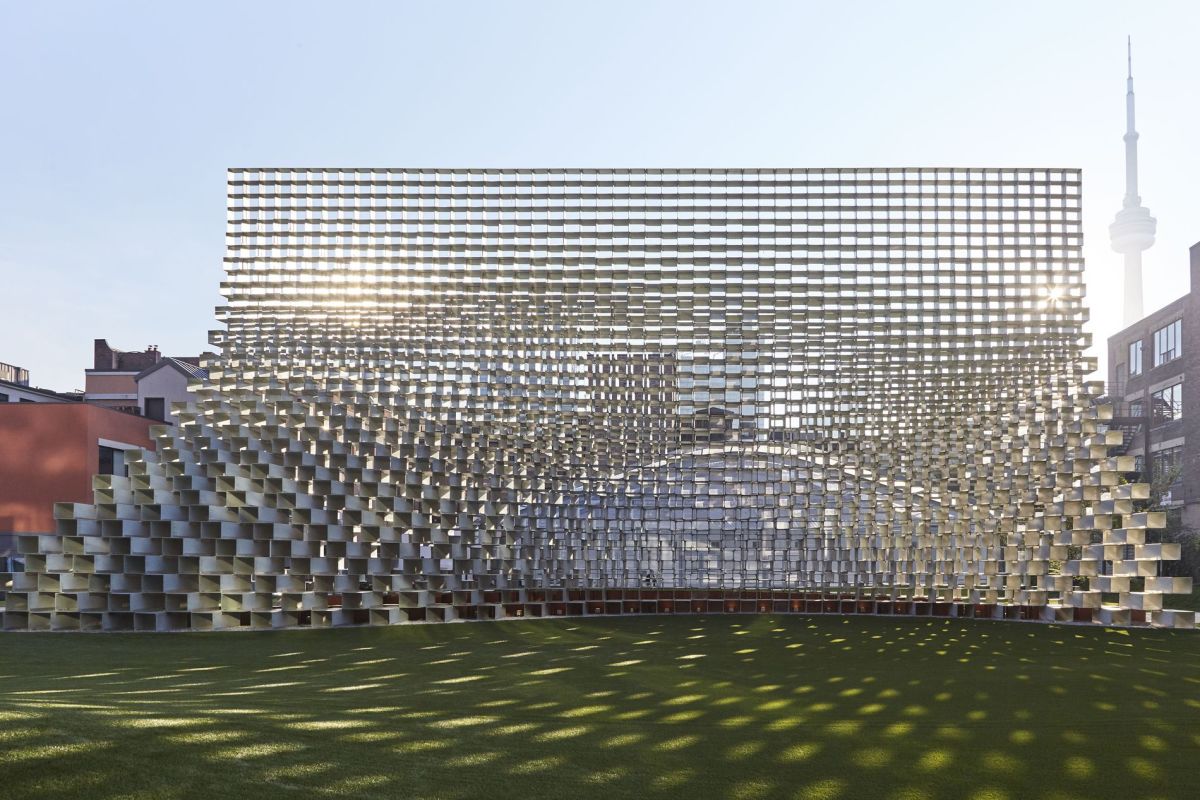

Mr. Ingels and his firm, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), have been exploring that question in a string of innovative buildings over the past decade – and now that effort is coming to downtown Toronto, in the form of a particularly radical building. After 2½ years of negotiations, the condo project Westbank King Street has been approved and is about to start sales. It’s being heralded by “Unzipped Toronto,” an exhibition in a BIG-designed pavilion that opens this week.

The new condo will be hard to miss. It could be the strangest residential building ever constructed in Canada. Certainly, it will set an interesting example for new housing. While new condos and apartments are often faulted for being soulless, this promises to be a carefully detailed building, a distinctive place, and a village that contributes to the larger city.

Habitat for Toronto

BIG is also making its mark on other Canadian cities, collaborating in each case with B.C.’s Westbank: The 52-storey Vancouver House recently topped off, and the office tower Telus Sky, Calgary’s third tallest building, opens to tenants this winter.

But the most interesting of them is the King Street project, by Westbank in partnership with Toronto office developers Allied Properties REIT. It was inspired by Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, the legendary assemblage of prefab boxes on Montreal’s harbour. Ian Gillespie of Westbank, the ambitious developer leading the King project, says he admires Habitat for its “ambition to create community” and because each of its units has its own identity – just like a single-family house. “If you live in a house, that house becomes part of who you are,” he argues. With King Street, “That is the ambition: that for residents, their home is unique to them.”

Like Habitat, the King Street building is configured as a series of “mountains,” irregular stacks of boxes that each contain a home or a piece of one. The residences rise up, over and around four century-old brick buildings, which will all be retained entirely or in large part. The BIG design borrows the peculiar genius of Mr. Safdie’s design by giving each home its own distinct expression, and its own terrace. As you step out from an apartment, you’ll be able to look across the way to wave to your neighbours. “Residents will be able to see each other and say hello to each other,” Mr. Ingels says.

Meanwhile, the interior spaces of each home and office unit are relatively straightforward. The condo floor plans are generally either square or L-shaped, with sensible rectangular rooms, and the leftover corners taken up by corridors or laundry rooms. They are eminently livable. This is typical of BIG’s work, which tends to juxtapose fantastic ambition with business savvy and technical expertise. (Their partners on the Toronto project are Diamond Schmitt Architects.)

A new model

Still: The design breaks a lot of rules. Which is why it took two years of difficult negotiations with city planners to reach approvals. “We wanted it to be quieter,” says Lynda MacDonald, a senior Toronto planner who was involved in overseeing the project. “It’s a very large project, and we wanted to make sure it respected the character of King Street.”

That heritage concern is reasonable, on a block with a fine collection of brick-and-beam warehouses and factories. Yet, planners can show an excessive deference to the idea of “context,” with bad – and dull – results. Two nearby condos are clad in brick, but they’re poorly detailed, neither interesting nor a match for Victorian craftsmanship.

BIG, and their clients, were ready to do something more thoughtful, but had no interest in blending in. After much back-and-forth, they’ve settled on glass block as the building’s main cladding material. Mr. Ingels refers back to Pierre Chareau’s Maison du Verre, the Modernist house completed in 1932 in a Paris courtyard. “The glass has a varied character,” he says. “It’s always changing, and there are different degrees of transparency and translucency that could be incredibly beautiful.”

Mr. Ingels, with his characteristic flair for metaphors, adds: “It will look a bit like an iceberg.”

The King Street project is also an ambitious experiment with urban design. There are basically two species of tower in Toronto: a midrise slab of six to 10 storeys, which steps back at the top; and a “tower-and-podium,” a model borrowed from Vancouver that combines a fat, squared-off base (or “podium”) with a tall, skinny residential tower. Both can work, but can also create the big-box blandness that many people dislike about new urban housing.

As for BIG, “We try to be informed by some of the qualities we perceive in the surroundings and take them one step further,” Mr. Ingels says. In this case, the important “quality” is the maze of laneways and courtyards on the site. The mountains will frame a central courtyard, which opens to the street to the north and towards a new park to the south. At ground level, the courtyard will run up against the facades of the heritage buildings, which will contain retail and office space; and the courtyard itself will feature a dramatic design by local landscape architects Public Work, including a graphic paving pattern that imitates 1950s terrazzo, and a misting device they call a cloudmaker. It will have restaurant patios, and there will be performances; Mr. Gillespie, whose company and partners will retain ownership of the retail and office spaces, promises a consistent slate of events. “It will be lively,” Mr. Gillespie says.

The landscape also extends, very significantly, up onto the fringes of the residences themselves. Each home will include a tree planted in a purpose-built, irrigated planter and a trellis planted with vines. In drawings, the building looks spectacularly green; Mr. Gillespie and Mr. Ingels each describe those flora as critical to the design. “Westbank, and we, are very committed to making this work,” Mr. Ingels says.

And yet even before all those trees grow in, the building will be distinctive and varied: terracing up and down, lifting up to create an arch over a pedestrian pathway. “It is not just a giant rectangle,” Mr. Ingels says. Rather, it is deliberately intended as a device to create all sorts of social interaction.

The Orestad experiment

Mr. Ingels and BIG have done this before. In the suburban Copenhagen neighborhood of Orestad, there is a cluster of four apartment buildings by BIG and by Mr. Ingels’s earlier firm. One of them, the Mountain Dwellings, is a stack of 80 apartments splayed atop a wedge-shaped parking garage. Each unit has a terrace with planter boxes, which – when I was there recently, nine years after the building was completed – looked remarkably verdant.

Not far away stands 8 House, the largest and the most famous of these projects. It’s the subject of a 2015 documentary, The Infinite Happiness, that depicts the building’s basement tinkerers and yoga classes.

This is where I met Fredrik Lyng and Gabrielle Nadeau, two young architects who work for BIG and live in 8 House. They and their two young daughters live in a townhouse on the 10th floor; each day, they make their way home along a gentle outdoor ramp that winds upward from the street, past their neighbours’ patios and around green courtyards.

“I feel like we are part of a 3-D community,” Ms. Nadeau, who grew up in Quebec, told me in her living room. “I see 8 House as a village much more than a building.”

They had just moved a few doors down into a new apartment, slightly different from their old one with a bonus living room tucked behind an elevator. The building is full of such variations, which allow residents “to find, much more precisely, what they’re looking for,” Mr. Ingels tells me. “No doubt it would be simpler to repeat the same apartment, but there is a quality in diversity.”

As we walked down the ramp toward dinner at 8 House’s (very good) restaurant, I could take in the suburban normalcy and also the 3-D complexity of the architecture. Neighbours were grilling meat or sitting on their patios with glasses of wine; we strolled by on the paved, snaking path, moving through part of the building in a tunnel. Then we veered off the path and descended a vertiginous flight of stairs, passing by a couple watering their garden and a man reading the newspaper, and looking out across the adjacent wetlands.

So how will this model – of intimacy and spatial complexity and surprising juxtapositions – work in an old part of a North American city? Mr. Ingels is optimistic. “I think one power architecture can have,” Mr. Ingels says, “is to create different niches where life can occur, and create encounters so that the community can be more tightly knit.” In Toronto, we’ll see.